Author: [Anonymous]

Date: July 29, 1775

“A gentleman is arrived in town, who was present at the action on the 17th of June, at Charles Town, between the Provincials and the Regulars; he says, that nothing could exceed the intrepidity of the Americans; that the King’s forces have intrenched themselves at Charles-Town, which was little more than a heap of smoking ruins; and that the Provincials were strongly posted on an eminence, at no very great distance from the former, but so advantageously situated, as to be able at any time to prevent a possibility of the King’s troops from penetrating into the country. He further says, that the celebrated Dr. Warren, who commanded the Provincial trenches at Charles-Town, while he was bravely defending himself against several opposing Regulars, was killed in a cowardly manner by an officer’s servant, but the fellow was instantly cut to pieces; six letters were found in the Doctor’s pocket, written from some gentlemen in Boston, who were immediately taken into custody, and whose situations when he came away, were so perilous and critical, that their friends every moment feared their executions from some arbitrary and illegal sentence of the new adopted law martial. He also adds, that at a council of war held at Boston, the officers were unanimously of the opinion, that it required no less a number than thirty thousand men to make any effectual advances, the American army were so exceedingly numerous, strongly entrenched, well supplied, and resolutely determined to oppose any hostile movements of the regular troops.

The good policy of the Americans is particularly conspicuous in their preferring old experienced officers to young, raw, and foolhardy striplings.”

Source: Morning Chronicle, London, July 29, 1775

Commentary: This account of Warren’s death near the redoubt on Breed’s Hill at the climax of the battle on June 17, 1775 is likely to be the correct one among a dozen or more widely divergent eyewitness versions. It is corroborated by forensic evidence derived from photographs of Warren’s remains. I incorporate this scenario into my biography of Dr. Joseph Warren.

This story is among the first newspaper reports breaking news in London of what came to be known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. The unnamed informant was someone who departed Boston in late June or early July and was sympathetic to the Americans. The trans-Atlantic transmission of this news was notably faster than a more typical six weeks.

Joseph Warren’s battlefield death is described in heroic terms to the British audience. The scenario of the fatal stroke being delivered by an officer’s servant is the most consistent, among the contradictory and widely divergent descriptions of Warren’s demise, with the modern forensic analysis of old pictures of the fatal wound. This is the only such account involving an officer’s weapon, whose caliber is notably smaller than the British infantry Brown Bess.

Taking this description of Warren’s demise at face value, Warren was recognized on the battlefield. Seemingly against the will of superiors, a British officer’s servant fatally shoots Warren “in a cowardly fashion,” presumably using the officer’s pistol or fusil. I interpret the pejorative “cowardly” to mean that Dr. Warren could have been overpowered at that point and the chivalric action of the unnamed officer would have been to take the Patriot leader as a prisoner. Warren’s assailant in turn is “cut to pieces,” a phrase I interpret to be more figurative than literal. The officer’s servant apparently was killed by one of the few remaining Americans, perhaps by sword, as lack of ammunition had precipitated the American retreat.

Early biographer Richard Frothingham quoted this same British account, identifiable by its distinctive choice of words. Otherwise meticulous Frothingham noted it simply as “British Letter, July 5, 1775” (Frothingham, Richard. Life and Times of Joseph Warren. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1865, pp. 519-520) as one alternative to his preferred description of Warren’s last moments. The manner in which Frothingham footnoted the letter implies that he may have accessed the actual ms, or perhaps a more complete newspaper printing of it, rather than as it is extracted here in the Morning Chronicle. If so, locating the letter would be of particular interest to historians of Bunker Hill. Its resonance with new forensic findings lends the unnamed letter’s author credibility and authority for other interesting details he may have written, and may be found nowhere else.

The account also includes compromising letters from Boston informants found in Warren’s pockets. This is consistent with both Patriot and Loyalist contemporary accounts of summary arrests and imprisonment of several suspect Bostonians, including James Lovell and John Leach, in the days following the Battle of Bunker Hill.

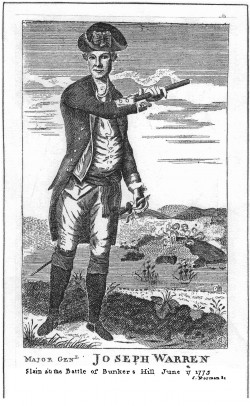

The illustration of Joseph Warren is by Boston engraver John Norman. It first appeared in An Impartial History of the War in America. Boston: Nathaniel Coverly and Robert Hodge, 1781; and “Memoirs of Major-General Warren” Boston Magazine (1784): pages 221-222. Though an early depiction of Joseph Warren in print, it fancifully shows him in a Continental Army general’s uniform. Artist Norman may have modeled his likeness of Warren from a John Singleton Copley portrait and additionally may have met his subject prior to mid-June 1775.

Follow

Follow