Date: June 17, 2014

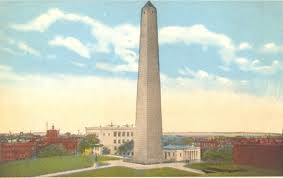

Bunker Hill Monument, Charlestown, MA

Samuel A. Forman

In many of our annual commemorations, dating back at least to 1857, representatives of the United Kingdom have joined us as here at the Bunker Hill Monument as honored guests. I have heard wits remark on this presence as the British indulging, doubtless with stiff upper lip, their former colonists as local celebrants hail a dramatic step toward American independence from them. Or perhaps that they are here to remind us that this was a British military victory, if a tactical reverse for them. But there is a more serious side to things, as we consider the valor and carnage of that day in mid-June of 1775, when an effusion of American and British blood forever marked this hill as hallowed ground.

In early 1775 Americans considered themselves as Britons, entitled to full British Constitutional rights and representative government. In this they were close political kin to British Whigs, with whom they aligned to defuse previous crises concerning the Stamp Tax and Townshend duties. The King’s Tory ministry did not see things that way. When Americans protested with the Boston Tea Party, the Tory ministry answered with draconian measures. Instead of bringing British Americans back into the fold as dutiful and subordinate colonials, the policy instead escalated differences into fighting at Lexington and Concord and, two months later, on this very spot.

Joseph Warren, a hero of the Battle of Bunker Hill, just 3 months prior, captured in his Boston Massacre Oration the challenges of that historical moment:

”The hearts of Britons and Americans, which lately felt the generous glow of mutual confidence and love, now burn with jealousy and rage. Though, but of yesterday, I recollect (deeply affected at the ill boding change) the happy hours that past whilst Britain and America rejoiced in the prosperity and greatness of each other (heaven grant those halcyon days may soon return.) But now the Briton too often looks on the American with an envious eye taught to consider his just plea for the enjoyment of his earnings, as the effect of pride and stubborn opposition to the parent country. Whilst the American beholds the Briton as the ruffian, ready first to take away his property, and next, what is still dearer to every virtuous man, the liberty of his country.”

“…But the royal ear, far distant from this western world, has been assaulted by the tongue of slander; and villains, traitorous alike to king and country, have prevailed upon a gracious prince to clothe his countenance with wrath, and to erect the hostile banner against a people ever affectionate and loyal to him his illustrious predecessors of the house of Hanover. Our streets are again filled with armed men; our harbour is crowded with ships of war; but these cannot intimidate us; our liberty must be preserved; it is far dearer than life, we hold it even dear as our allegiance; we must defend it against the attacks of friends as well as enemies; we cannot suffer even Britons to ravish it from us.”

Warren spoke to his present while being mindful of providing the foundation for a solid future.

He continued: “Where justice is the standard, heaven is the warrior’s shield… Britain, united with these colonies, by commerce and affection, by interest and blood, may… be the seat of universal empire. But should America, either by force, or those more dangerous engines, luxury and corruption, ever be brought into a state of vassalage, Britain must lose her freedom also.

But, if from past events, we may venture to form a judgment of the future, we justly may expect that the devices of our enemies will but increase the triumphs of our country. I must indulge a hope that Britain’s liberty, as well as ours, will eventually be preserved by the virtue of America.”

I cannot but think Warren prescient when considering the dynamics between Great Britain and the United States from struggling together in the trenches of World War I, to joining Britain in her “finest hour” opposing international enemies of Liberty and Freedom during World War II, to our being closest friends and allies in the Twenty-First century War on Terror.

Considering what transpired here on June 17, 1775, eight long years of a Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812 a generation later, that bond between countries, peoples, and philosophies, remains a testament to the durability of human nature and the bedrock principles linking the United States and Great Britain.

Source: Joseph Warren, Boston Massacre Oration [March 6, 1775]. In: John Collins Warren Papers. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. Ms N-1731 Box 1A

Commentary: I delivered these remarks as one of the speakers at the Bunker Hill Monument on the 239th anniversary of the battle. Preceding Boston’s Mayor Walsh, these words were of particular interest to the British Consul General for Boston, who attended.

Follow

Follow