Commentary: Previously we published Frederick C. “Rick” Detwiller’s assertion, accompanied by compelling circumstantial evidence, that controversial Patriot James Swan (1751-1830) is depicted as the heroic protector of the mortally wounded Dr. Joseph Warren in the central vignette of John Trumbull’s iconic historical painting Bunker’s Hill. The painting begs understanding on several levels, as it was, and remains, important to the understanding of a pivotal early Revolutionary War event; to influencing subsequent historiography of the era, and to casting a distinctly American heroic iconography of Revolutionary War personalities and events.

I summarize Rick Detwiller’s assertion identifying James Swan in Trumbull’s picture this way:

– The coatless young man’s looks are consistent with a Gilbert Stuart portrait of Swan made in 1795,

– Swan filed a claim for material losses as a volunteer while “accompanying Dr. Joseph Warren” into the Battle of Bunker Hill. He literally lost his coat (but not his shoes) and damaged his musket.

– Swan and Trumbull had opportunities to interact during the Siege of Boston and circa 1777-78 when they both were members of the same social club in Boston and Trumbull was an aspiring painter. Trumbull had ample opportunity to hear Swan’s story of accompanying Joseph Warren to Bunker Hill back in 1775. That association would have enhanced Swan’s stature, as Warren and Bunker Hill had already attained legendary status during the Revolutionary War.

– Later, in Europe during the latter 1780s and 1790s, James Swan shared acquaintances with many of the same influential people as did John Trumbull. A direct letter between the two survives from 1799.

– Swan’s long imprisonment beginning in 1808 in France, despite his personal contacts with Thomas Jefferson and Lafayette, suggests to Rick that the legacy of the then-controversial Swan was suppressed deliberately by forcing his anonymity in Trumbull’s painting. This assertion touches on unseen hands of shadowy, offended Masons and Illuminati. Personally, conspiracy theories do not much appeal to me unless they are corroborated by documentary evidence and are placed in context of other relevant agency and trends. One does infer that James Swan’s financial manipulations from the late 1780s onward may have gotten him into trouble with some of his investors. Rick asserts further that Swan may have been black-balled in this visual realm. Many of the actors in this drama – including Trumbull, Swan, Dr. Warren, Lafayette, etc., were Masons.

– The depiction of the Warren’s coatless protector is so central to Bunker’s Hill, that it had to have been some real person. If not Swan, then who?

In my and J.L. Bell’s judgments, the figure is not Swan, but rather an anonymous American militiaman who counters the bayonet thrust of the equally anonymous British grenadier. Much as we are intrigued by Rick Detwiller’s thesis and are impressed by his research into little known primary sources, we believe that it is undermined by both John Trumbull’s own notations and what we know of his painterly methods.

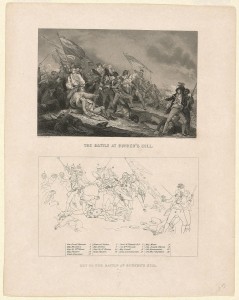

The painting itself and its associated sketches provide visual evidence arguing for an anonymous militiaman versus James Swan, or anyone in particular. Preliminary sketches, from the summer and fall of 1785 show that overall point of view and positioning of the figures were first and foremost on Trumbull’s mind. The central vignette of the dying Warren is reminiscent of a fighting version of Michelangelo’s Pieta sculpture. Once Trumbull had set upon the overall scene and the arrangement of figures, then he captured portraits of key individuals. Not everyone is a real person; most figures sustain the visual arrangements and were meant to be generic militiamen and opposing British soldiers.

Art historians, based on Trumbull’s 1843 autobiography and earlier primary sources, state that Trumbull obtained such likenesses variously from life, from close relatives in the case of the deceased, or from other artists’ portraits. The source of his portrait of Warren is unknown. I have conjectured that Trumbull derived it from J.S. Copley’s studio portrait, made years earlier in Boston from life. Both Copley and Trumbull were associated, and resident for a time, in expatriate painter’s Benjamin West London studio.

Timing enables us to focus the discussion. According to Trumbull’s autobiography, he finished with Bunker’s Hill by mid-1786, having begun layout sketches the previous autumn. He makes much in the autobiography of being coached immediately by Benjamin West on how to monetize the picture via an engraved version by subscription. We can tell from the first issued engraving (1798) and subsequent painted copies, that Trumbull froze the composition and portraits to that original painting of 1785-86.

That was before Swan apparently got into trouble and left Massachusetts for France. I conclude that interactions among Swan, Trumbull, and possibly invidious conspiracies are irrelevant after 1786. The coatless militiaman was already in the picture.

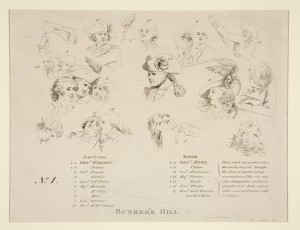

Trumbull, with an eye toward gaining subscribers for his series of engravings of his historical paintings, was collecting subscriptions for them by 1790, if not earlier. Trumbull’s earliest version of the key to Bunker’s Hill, dated about 1790, identifies key historical figures.

In this rarely seen version of the visual key, Trumbull placed an asterisk beside those named Americans and British, further distinguishing the seven of seventeen that he presented as authentic likenesses. The seven named as authentic likenesses include General Warren, General Putnam, General Howe, General Clinton, Major Pitcairn, Major Small, and Lieutenant Pitcairn. No James Swan. Note also that Colonel Knowlton and a few lesser known Patriots are listed, but are by default presented as speculative portraits.

Later versions of the visual key by Trumbull name the notables, but do not distinguish true versus speculative likenesses. This may have been a strategic omission by Trumbull.

By writing nothing to repudiate the inference, prospective buyers would assume that all the likenesses of important people were true ones (as is apparently the case with Trumbull’s Signing of the Declaration of Independence). Even thoughtful observers like Mr. Detwiller can be forgiven for going one erroneous step further – that every figure in the painting is the true portrait of an actual person present at the battle. However, the painting was executed ten years after the battle by an artist working from distant direct observation, on accounts of the action circulating after the fact, and within the expectations of late 18th century heroic historical genre painting.

Other aspects of the “Swan thesis” are suspect. True, the patriot of Bunker’s Hill lost his coat, just as documented in James Swan’s January 1776 claim for reimbursement. But he was not the only one to have filed such claims associated with equipment losses at Bunker Hill. So numerous and detailed are such claims, that reenactors and students of material culture study these claims for insights into clothing and materials militia men owned and used at that time. With respect to losing a coat in the chaotic retreat, James Swan was e pluribus unum.

J.L. Bell points out that the coatless protector of Warren is also shoeless. From the standpoint of visual representation, we do not expect a young gentleman to be presented as shoeless. Nor did the historical James Swan claim that he lost his pair of shoes. Not many claimed lost shoes. People instinctively know that they can run faster in a pell-mell retreat with their shoes on.

Mr. Bell also posits a more plausible reason for James Swan’s long imprisonment than the work of Illuminati hidden hands who threw away the jailer’s key. “I suspect the key to Swan’s later story lies in French archives, not any that I can access. The legend that has come to us involves him refusing to pay an unjust debt and staying in prison on principle. But that length of confinement suggests mental illness or something similar. Without local documents, I doubt we could break through the wrapping of legend.”

As I think about this, there are two distinct issues at play: In June of 1775 was Swan known to Warren and did he interact with Warren in some manner in the course of the Battle of Bunker Hill? Swan’s claim for losses and stories circulating by 1818 argue that he had been there, if not with Warren at the latter’s final moments. The other question is whether Trumbull included Swan in the picture Bunker’s Hill, painted in London in 1785-86; whether Trumbull sketched Swan from life for inclusion in the picture, and whether he thought it noteworthy enough to include it in the key to the picture. The weight of evidence leans against Swan being in the picture as either a stand-in or an actual likeness.

There is an outside chance that Rick Detwiller’s identification of Swan in the picture is indeed correct, and that J.L. Bell and I are wrong. Three aspects would have to align: 1.Trumbull obtained or had access to a likeness of Swan prior to 1786. 2.Trumbull deliberately painted Swan into the picture and did not change the likeness during over 40 subsequent years of authorized engravings and copies of the painting by the artist. 3.Trumbull forgot or suppressed any identification of Swan in keys to the painting. There is no evidence in surviving documentation for any of these points.

The exercise of learning more about James Swan was enlightening to me, regardless of whether or not he is depicted in Trumbull’s Bunker’s Hill. Swan is a very interesting character, one whose definitive biography has not yet been written. I hope Rick Detwiller or a reader of this blog will pursue and share some of the compelling and cryptic aspects of James Swan’s long life on both sides of the Atlantic.

Sources: John Trumbull Death of Major General Joseph Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775 Painted 1786 Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Accession 1832.1 (detail, and photo manipulation courtesy of web comic artist Lora Innes of the mortally wounded Joseph Warren from John Trumbull’s sketch and finished 1786 painting at Yale University Art Gallery)

John Trumbull Key to Death of Major General Joseph Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, 1790, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Accession 1946.9.2101; and Muller’s Key to Bunker’s Hill, early 19th c., YUAG Accession 1953.34.3

Entry for August 8, 1775, and Swan’s claim for losses at Bunker Hill. In: Massachusetts Provincial Accounts 1770-1776, Accounts of the Committee of Safety and Supplies. Boston: Massachusetts Archives, Vol. 255, microfilm reel 263, p. 822 James Swan re: Bunker Hill

Follow

Follow