“Worcester, April 24, 1775. Monday Evening.

Gentlemen: Mr. S. Adams and myself, just arrived here, find no intelligence from you, and no guard. We just hear an express has just passed through this place to you, from New York, informing that administration is bent upon pushing matters; and that four regiments are expected there. How are we to proceed? Where are our brethren? Surely, we ought to be supported. I had rather be with you; and, at present, am fully determined to be with you, before I proceed. I beg, by return of this express, to hear from you, and pray, furnish us with depositions of the conduct of the troops, the certainty of their firing first, and every circumstance relative to the conduct of the troops from the 19th instant, to this time that we may be able to give some account of matters as we proceed, especially at Philadelphia, also, I beg you would order your secretary to make out an account of your proceedings since what has taken place; what your plan is; what prisoners we have, and what they have of ours; who of note was killed, on both sides; who commands our forces, &c.

Are our men in good spirits? For God’s sake do not suffer the spirit to subside, until they have perfected the reduction of our enemies. BOSTON MUST BE ENTERERED. The troops must be sent away, or ____________. Our friends are valuable. BUT OUR COUNTRY MUST BE SAVED. I have an interest in that town. What can be the enjoyment of that to me, if I am obliged to hold it at the will of Gen. Gage, or anyone else? I doubt not your vigilance, your fortitude, and resolution. Do let us know how you proceed. WE MUST HAVE THE CASTLE [William] – the ships must be _______. Stop up the harbor against large vessels coming. You know better what to do that I can point out. Where is Mr. [Thomas] Cushing? Are Mr. [Robert Treat] Paine and Mr. John Adams to be with us? What are we to depend upon? We travel rather as deserters, which I will not submit to. I will return and join you, if I cannot detain this man, as I want much to hear from you. How goes on the [provincial] Congress? Who is your president? Are the members hearty? Pray remember Mr. S. Adams and myself to all friends. God be with you.

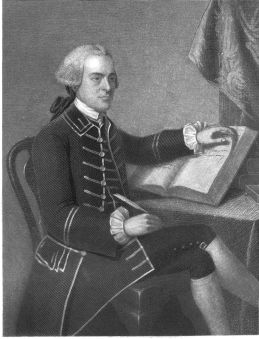

I am, gentlemen, your faithful and hearty countryman John Hancock.

To the Gentlemen Committee of Safety.”

Source: Quoted in William Wheildon’s New History of the Battle of Bunker Hill. 2nd ed. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1875, page 5. A more complete transcription with different emphasis appears in A.E. Brown’s John Hancock: His Book: Lee and Shepard, 1898, pp. 196-197, where it is identified as having appeared in the New England Magazine (undated). I am unaware of the present location of the manuscript.

Commentary: With gaps and capitalization reproduced from the original, this draft letter reflects the urgency and shrillness of the times. Samuel Adams was in the company of Hancock, both escaping the violence at Lexington on April 19th and endeavoring to travel to Philadelphia for the Continental Congress. Presumably these also capture the sentiments of Samuel Adams. Hancock’s admonition to Joseph Warren and the Massachusetts provincial militia leaders to take Boston back from the British by direct assault, in the face of the combined might of British land and naval forces, was impractical and would have been doomed to defeat. It would have inflicted irreparable harm to the Patriot cause by demonstrating the futility of armed resistance and painting Massachusetts Patriots as warlike radicals at a time when many individual colonial leaders in other colonies were not yet convinced of the necessity of sustained armed conflict.

Hancock’s aggressive opinion at this juncture is little recognized in popular histories of the era. It is consistent with an episode related years later by Benjamin Rush’s son and analyzed recently by J.L. Bell in his blog. In a weighty discussion of just a few months after this letter was written, when Hancock was then president of the Second Continental Congress and George Washington was recently appointed general of the Continental Army, Hancock was supportive of a potential attack on occupied Boston. Though such an assault would likely reduce the city to ashes, and destroy his real estate and business holdings there, he firmly supported the strategy for the greater good. Several 19th century historians celebrated Hancock for this stance, some offering dramatic direct quotes of Hancock. While the exact wording of those quotations are suspect, they capture Hancock’s fighting spirit of this primary source.

Follow

Follow