[to Samuel Adams, en route to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia]

“Boston, 21 Aug. [1774]

My Dear Sir, – I received yours from Hartford, and enclose you the vote of the House, passed the 17th of June. I shall take care to follow your advice respecting the county meeting, which, depend upon it, will have very important consequences. The spirits of our friends rise every day; and we seem animated by the proofs, which every hour appear, of the villainous designs of our enemies, which justify us in all we have done to oppose them hitherto, and in all that we can do in future. A non-importation and non-exportation to Britain, Ireland, and the West Indies, is now the most moderate measure talked: it is my opinion, that nothing less will prevent bloodshed two months longer. The non-importation and non-exportation to Britain and Ireland ought to take place immediately, -to the West Indies not until December next; because, should the non-exportation to the West Indies take place immediately, thousands of innocent people must inevitably perish: whereas, if it takes place at some distance, they, and the proprietors of the islands, may use their influence to ward off the blow; and; if they fail in that, they may come to the continent, where they will be treated with humanity. [By] stopping the exportation of flaxseed to Ireland, and giving them immediate notice, they may obtain a repeal of the Act soon enough to get their supply before sowing-time. This stoppage of exportation of flaxseed will not fall heavy upon any one in this country, as scarcely any farmer raises more than four, six, or eight bushels; but it will throw a million of people in Ireland out of bread. There are about one hundred thousand acres of land sowed in Ireland with flaxseed every year; and it is computed, that, with dressing and spinning, weaving, bleaching, &c., ten persons are employed by every acre; and the ministry will not find it easy to maintain so many persons in idleness, especially as the national revenue, if computed (as the best writers have computed) at eight millions sterling, will be one eighth part lost by the loss of their trade with America and the West Indies. In my next, I will endeavor to make some calculations of the interest which the British nation have in the West Indies and Ireland; also how many Irish peers and peers of Great Britain: and, if I can (though I hardly know how to go about it), will give some pretty near guess at the number of members in the House of Commons, whose chief fortunes lie in Ireland and the West Indies. I enclose you all the papers, as far as they are printed. I think nothing material is omitted. The extract of a letter from London, dated June first, is from Mr. Sheriff Lee. The lord said to be virulent against America, in the cabinet, is Dartmouth, in the letter. The lord said to be brought over to American justice is Temple. The letter was written to the Hon. Mr. Cushing.

I have now a matter of private concern to mention to you, by the desire of Mr. Pitts. Our friend, Mr. William Turner, has, as you know, been persecuted for his political sentiments, and ruined in his business. The dancing and fencing master, named Pike, in Charleston, South Carolina, is about leaving the school, and has invited Mr. Turner to take his place. I am myself, and I know you are, always deeply interested for the prosperity of persons of merit, who have suffered for espousing the cause of their country. If you can, by giving Mr. Turner his true character, interest the gentlemen with you in his favor, you will do a benevolent action, and oblige Mr. Pitts, Mr. Turner, and myself. If they could be induced to write to their friends, and know what encouragement he might expect, it might save him the expense of a journey which he can ill afford to take.

I am, dear sir, your most obedient servant, J. W.

P.S. – Please to make my respectful compliments to your three fellow-laborers. As far as I have been able to get information, their families and friends are in health. Let them know that I consider every thing I write to one of you is written to all. Great expectations are formed of the spirited resolves which the congress will pass relative to our traitors by mandamus.”

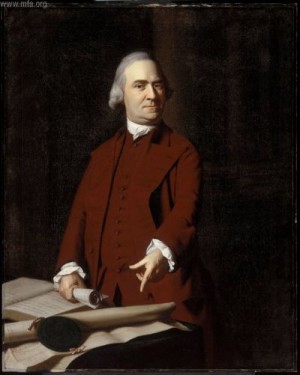

Source: Samuel Adams Papers 1635-1826. In Wells and Bancroft Collection. New York: New York Public Library. The text also appears in Frothingham, Richard. Life and Times of Joseph Warren. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co., 1865, p. 343-344. Dated apparently in error as 24 August 1774, the text also appears in William V. Wells’ The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., Vol. II, pp. 225-226. The 1772 portrait of Samuel Adams is by J.S. Copley, courtesy of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Commentary: Letters exchanged between Samuel Adams and his political protégé Joseph Warren during the summer of 1774 are revealing both of behind the scenes aspects of the fraught political situation and hints at their personal relationship. Adams was away from Boston at the June meeting of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, convened in Salem; and then off to Philadelphia for the First Continental Congress. Adams departed Massachusetts for the congress by mid-August. The “three fellow-laborers” referred to by Warren are the Massachusetts delegates to the Continental Congress.

In this communication Warren, in modern terms, is playing the policy wonk to Samuel Adams concerning the rationale, kind, and timing of proposed inter-colonial cooperation for a boycott of British goods and commerce. Warren is sensitive to potential collateral damage in the Atlantic World to Irish farmers dependent on American flax seeds for a key cash crop.

In an informal style suggestive of an easy familiarity, Warren relates intelligence of Tory and Loyalist activities as well as soliciting intervention on behalf of a distressed friend and Patriot, William Turner. The relationship between the elder Adams and Joseph Warren presumably possessed these characteristics for years, but only periods of geographic separation was there a need to commit interactions to writing.

During this period Joseph Warren began to step out from the shadow of his political mentor Samuel Adams. By the convening of the Suffolk Convention in early September 1774, his intervening to defuse the Cambridge Alarm that same week, and his triggering of the events of April 19, 1775, Warren’s penchant for decisive, inspiring, and improvisational leadership came to fruition just as events spiraled toward war.

Follow

Follow