Date: mid-to-late 1775 and showing the 1776 date.

An Account of the Commencement of Hostilities between Great Britain and America, in the province of Massachusetts Bay, by the Rev. Mr. William Gordon, of Roxbury, in a letter to a gentleman in England.

[Continued from part I, found here] Before Major Pitcairn arrived at Lexington signal guns had been fired, and the bells had been rung to give the alarm: Lexington being alarmed, the train band or militia, and the alarm men (consisting of the aged and others exempted from turning out, excepting upon an alarm) repaired in general to the common, close in with the Meeting house, the usual place of parade; and these were present when the roll was called over, about one hundred and thirty of both, as I was told by Mr. Daniel Harrington, Clerk to the company, who further said, that the night being chilly, so as to make it uncomfortable being upon the parade, they having received no certain intelligence of the regulars being upon the march, and being waiting for the same, the men were dismissed to appear again at the beat of drum. Some who lived near went home, others to the public house at the corner of the common.

Upon information being received about half an hour after that the troops were not far off; the remains of the company who were at hand collected together, to the amount of 60 or 70, by the time the regulars appeared, but were chiefly in a confused state, only a few of them being drawn up which accounts for other witnesses making the number less, almost 30. There were present, as spectators, about forty more, scarce any of whom had arms. Gage’s printed account, which has little truth in it, says, that Major Pitcairn galloping up to the head of the advanced companies, two officers informed him, that a man (advanced from those that were assembled) had presented his musquet, and attempted to shoot(?) them, but the piece flashed in the pan. The simple truth I take to be this, which I received from one of the prisoners at Concord in a free conversation, one James Marr, a native of Aberdeen, in Scotland, of the 4th regiment, who was upon the advanced guard, consisting of six, besides a sergeant and corporal. They were met by three men on horseback before they got to the next meeting-house a good way; an officer bid them stop; to which it was answered, you had better turn back, for you shall not enter the town; when the said three persons road back again, and at some distance one of them offered to fire, but the piece flashed in the pan, without going [ ] [ ][ ] Marr, whether he could tell if the piece was designed at them or others, or to give an alarm ? he could not say which. The said Marr further declared, that when they and the others were advanced, Major Pitcairn said to the Lexington company (which, bye the bye, was the only one there) Stop you rebels! And he supposed that the design was to take away their arms; but upon seeing the regulars they dispersed, and a firing commenced but who fired first he could not say.

The said Marr, together with Evar(?) Davies, of the 23rd, George Cooper of the 23rd, and William McDonald of the 38th, respectively assured me in each other’s presence, that being in the room where John Bateman, of the 52nd, was (he was in an adjoining room, too ill to admit of my conversing with him) they heard the said Bateman say, that the regulars fired first, and saw him go through the solemnity of confirming the same by an oath on the Bible.

I shall not trouble you with more particulars, but give you the substance as it lies in my own mind, collected from the persons whom I examined for my own satisfaction. The Lexington company, seeing the troops, and being of themselves so unequal a match for them, were deliberating for as few moments what they should do, when several dispersing of their own head, the Captain soon ordered the rest to disperse for their own safety. Before the order was given, three or four of the regular officers, seeing the company as they came up on the rising ground on this side the meeting, rode forward, one or more round the meeting-house, leving it on the right hand, and so came upon them that way; upon coming up, one cry’d out, “you damn’d rebels lay down your arms;” another, “stop you rebels;” a third, “disperse you rebels;” &c. Major Pitcairn, I suppose, thinking himself justified by parliamentary authority to consider them as rebels, perceiving that they did not actually lay down their arms, observing that the generality were getting off, while a few continued in their military position, and apprehending there could be no great hurt in killing a few such Yankees, which might probably, according to the notions which had been instilled into him by the tory party of the Americans being paltroons, to end all the contest, gave the command to fire, then fired his own pistols, and forced the whole affair a-going. There were killed at Lexington eight persons, one Parker, and two or three more, on the common: the rest on the other side of the walls and fences while dispersing. The fusiliers fired at persons who had no arms. Eight hundred of the best British troops in America having thus nobly vanquished a company of non-firing Yankees while dispersing and slaughtered a few of them by way of experiment, marched forward in the greatness of their might to Concord.

The Concord people had received the alarm, and had drawn themselves up in order of defence; upon a messenger’s coming and telling them that the regulars were three times their number, they judiciously changed their location, determining to wait for reinforcements from the neighbouring towns, which were now alarmed; the Concord company retired over the North bridge, and when strengthened returned to it, with a view of dislodging Capt. Laurie, and securing it for themselves. They knew not what had happened at Lexington, and therefore orders were given by the commander not to give the first fire; they boldly marched towards it, though not in great numbers, and were fired upon by the regulars, by which fire a Captain belonging to Acton was killed, and I think a private. Lieut. Gould, of the regulars, who was at the bridge, was wounded and taken prisoner, has deposed that their regulars gave that first fire there and their soldiers that knew anything of the matter made no scruple of owning the same that Mr. Gould deposed. After the engagement began the whole detachment collected together as fast as it could. The detachment when joined by Capt. Parsons, made a hasty retreat, finding by woful experience that the Yankees would fight, and that their numbers would be continually increasing. The regulars were pushed with vigor by the country people, who took the advantage of wall, fences, &c. cut chase that could get up to engage were not upon equal terms with the regulars in point of number any part of the day, though the country was collecting together from all quarters, and had there been two hours more for it, would probably have cut off both detachment and brigade, or made them prisoners.

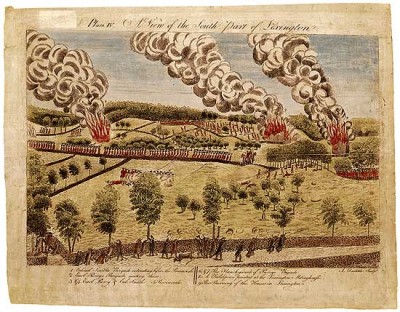

The soldiers being obliged to retreat with haste to Lexington had no time to do any considerable mischief. But a little on this side of Lexington meeting-house, where they met the brigade, with cannon, under Lord Percy, [ ] changed. The inhabitants had quitted their houses in general upon the road, leaving almost every thing behind them, and thinking themselves well off in escaping with their lives. The soldiers burnt in Lexington, three houses, one barn and two shops, one of which joined to the house and a mill-house adjoining to the barns: Other houses and buildings were attempted to be burnt and narrowly escaped. You would have been shocked in the destruction which has been made by the regulars, as they are so-called, had you been present with me to have beheld it. Many houses were plundered of everything valuable that could be taken away, and what could not be carried off was destroyed. The troops at length reached Charlestown, where there was no attacking them with safety to the town, and that night and the next day crossed over in boats to Boston, for the people poured down in so amazing a manner from all parts, for scores of miles all around, even the grey-haired came to assist their countrymen, the General was obliged to set about further fortifying the town immediately at all points and places. The detachment while at Concord; disabled two 24 pounders, destroyed their carriages, and seven wheels for the same, with their limbers; sixteen wheels for two 4 pounders; 500 pounds of balls thrown into the river, wells and other places; and broke in pieces about 60 barrels of flour, half of which was saved. Apprehend upon the whole the regulars had more than 100 killed, and 150 wounded, besides about 50 taken prisoners. The country people had about 47 killed, 7 or 8 taken prisoners, and a few wounded.”

Source: Gordon, William: “An Account of the Commencement of Hostilities between Great Britain and America, in the Province of Massachusetts Bay” ” in: Stearns, Samuel, The North American Almanack, And Gentleman’s and Lady’s Diary, For the Year of our Lord Christ 1776, I. Thomas in Worcester [MA]; B. Edes, in Watertown [MA], and S. and E. Hall in Cambridge [MA], pages 5-15. The text and commentary appears in Murdock, Howard. 1927. “Letter of Reverend William Gordon, 1776.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society LX: 360-366. See also Commanger, Henry Steel, and Richard B. Morris. 1968. The Spirit of Seventy-Six – The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants. New York: Harper and Row. Extracted pp. 78-79. I have divided William Gordon’s account into two parts, the better to appeal to we modern readers possessing Twitter-like attention spans.

Commentary: This almanac was probably printed early in the Siege of Boston. By recounting a detailed account of the April 19, 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, but nothing of the June 17th action on Bunker Hill, one might assert that this account was composed in late spring, prior to the summer and autumn of 1775. The latest chronological internal reference is to General Gage’s Circumstantial Account, which became available in New England by early May 1775. Dating it on the cover to the following year, the time of a celestial almanac’s intended use, would have been typical of printing and sales practices of the time.

Similar accounts by William Gordon, differing in notable respects, appeared in colonial newspapers outside New England. As expounded upon by Todd Andrlik, our favorite authority on Colonial American newspapers, in the on-line Journal of the American Revolution, many of the newspaper accounts name Paul Revere as a notable person carrying the alarm and suggest more extensive military preparations than New England Patriot leaders would like to have been widely known.

A hint to more precise dating of the 1776 Stearns Almanac may come from its title page. Mr. Andrlik notes, in comments to his above-cited article, “Following the 2 May issue, the printers of the Essex Gazette moved their press from Salem to Cambridge, the HQ of the New England army, and began publishing the New-England Chronicle as of 12 May.” We note that one of the three publishers of the Stearn’s Almanac, S. and E. Hall of the Essex Gazette formerly of Salem, are listed as being in Cambridge.

I infer that this piece represents an evolving, semi-official Massachusetts Patriot narrative of events concerning the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. Pertinent aspects include:

- My inference that the timing of the writing of this piece was subsequent to the initial newspaper accounts, many of which were written by, or quoted, William Gordon and datelined May 17, 1775:

- Surviving documentation showing that William Gordon had Joseph Warren’s explicit permission to gather information on the Lexington and Concord actions in an effort independent of the official gathering of depositions. Note the resolve of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, May 12, 1775: “Resolved, That all persons who have the care of any Prisoners detained at Concord, Lexington, or elsewhere, be and hereby are directed to give the Rev. Mr. Gordon free access to them, whenever he shall desire it; and it is recommended to all civil Magistrates and others, to be aiding and assisting him in examining and taking Depositions of them and others, without exception.”

- This almanac account not naming Paul Revere nor any other Patriot beside Daniel Harrington of the Lexington Minutemen. In contrast, a number of British officers and captured enlisted men are named. In contrast, newspaper accounts do name Paul Revere and provide much more detail on Patriot organization and preparations.

- Shifting emphasis, including deletion of Revere’s name and exploits, in the almanac, as compared to the newspaper accounts, suggest that a kind of censorship was at work by Joseph Warren and his colleagues through interlocking roles in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, Committee of Safety, and Committee of Correspondence.

- Joint publishing by the three Patriot publishers of Stearn’s Almanac, all closely aligned with the Boston Patriot leaders whose ranking member on the scene was Joseph Warren, suggest that this is a semi-official version of events authorized by Patriot leaders confronting the British Army in Massachusetts. In 1773 Isaiah Thomas’ Massachusetts Spy and Hall’s Essex Gazette had experimented with cooperative printing of a Patriot response to a high profile speech by Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Follow

Follow