Author: Joseph Warren

Date: January 23-25, 1771

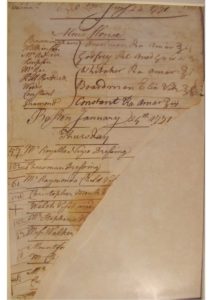

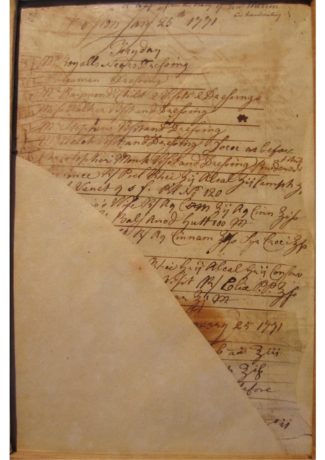

Source: Two sided day book page fragment in Joseph Warren’s handwriting, no signature. Image courtesy of Mr. John Quinlan, current private owner of the document. Sold by Skinner’s at their books and manuscripts auction 2571B as lot 131 on November 13, 2011 for $858. The auctioneer’s listing notes a prior purchase from Goodspeed’s, Boston in 1974. By notations in another hand on the manuscript, this page passed through the hands of 19th century collector Ellis Ames.

Discussion: I present here another fragment from Joseph Warren’s lost account book from 1771. If and when the pages covering the Boston Tea Party surface – November and December of 1773 – historians will have to rewrite the history of that pivotal event to include Joseph Warren’s role with more certainty than is currently warranted.

Though fragmentary, details of Joseph Warren’s medical practice, not otherwise available in primary sources, are revealed.

Fragment of Joseph Warren’s Missing Account Book. Image courtesy of John Quinlan

Fragment of Joseph Warren’s Missing Account Book. Image courtesy of John Quinlan

“Mr. Royall’s negro” may have been an enslaved servant of the well-off Loyalist Royall family. The Royall mansion and slave quarters survive in Medford as a museum operated by Tufts University: http://www.royallhouse.org/. We note that Warren cared for people of color in the order in which they presented and according to clinical need. Though raised with two enslaved servants in his childhood household in Roxbury, and himself the owner of an enslaved Black teen in 1770, there was no “back of the bus” in Dr. Joseph Warren’s clinical care.

This account book fragment, not heretofore generally known to historians, confirms that Dr. Joseph Warren provided clinical care for Christopher Monk almost a year after the March 5, 1770 Boston Massacre. J.L. Bell in his Boston1775 blog discussed the unfortunate life of Christopher Monk, who was wounded at the Boston Massacre. The Boston Gazette of March 12, 1770 described the teenager Monk’s wounding and initial fears, played up in Patriot propaganda but apparently well grounded in clinical reality, that Monk would soon die:

“A lad named Christopher Monk, about 17 years of age, an apprentice to Mr. Thomas Walker, Shipwright; wounded, a ball entered his back about 4 inches above the left kidney, near the spine, and was cut out of the breast on the same side; apprehended he will die.”

Any penetrating chest wound was expected, even under the best medical and surgical care, to prove fatal during the 18th century. Instead, Monk lingered with continuing complications of the wound. Monk and Walker do not appear in Dr. Joseph Warren’s surviving 1774-1775 account day book, so Monk’s care may have been transferred to another physician(s) by then. The unfortunate Monk seems to have become totally disabled, and a living Patriot exhibit recalling the horrors of the Boston Massacre. Thomas Walker, his employer, assumed financial responsibility for Monk’s clinical care, for which he sought reimbursement from the Town of Boston in 1774. The Town allocated funds toward Monk’s relief by direct payments to the young man, but apparently did not redress Thomas Walker’s personal request for reimbursement.

The top of the account book page dated Wednesday, January 23, 1771 lists patients seen and prescriptions dispensed by Dr. Warren at the Alms’ House. Warren was the designated physician to the Boston Alms’ House from 1769-1772. It was a prestigious political appointment enabling the physician a benevolent opportunity to provide clinical care to needy and presumably appreciative people while simultaneously enjoying an assured income. The designated physician could expect fees for doctor visits and dispensed prescriptions at the Alms’ House would be fully reimbursed by the Town. That was a more assured situation than collections against private patient billings. Appendix I of my biography of Dr. Warren provides a quantitative analysis, based on forensic accounting reconstruction of Warren’s day journal and account books, of Warren’s billings and actual collections across the entirety of his medical career, from 1763 until the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in April 1775.

Follow

Follow